Thursday, December 5, 2024

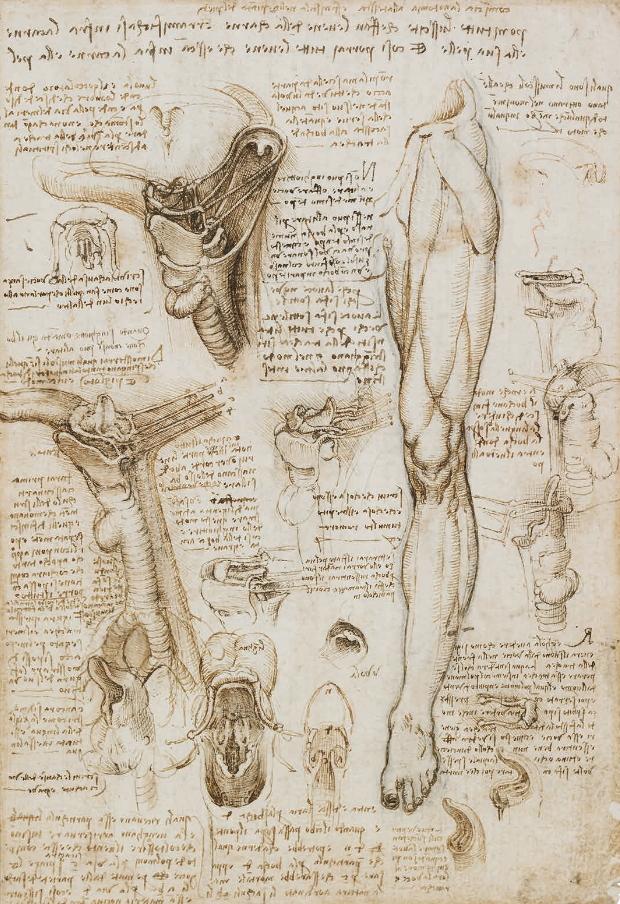

A few examples of Leonardo's drawings, with self-portrait at age 60 in the centre. His notebook manuscripts are held in both public and private collections, notably by Bill Gates, the Ambrosiana, and the Royal Collection Trust.

“...the greatest geniuses sometimes accomplish more when they work less, since they are searching for inventions in their minds, and forming those perfect ideas which their hands then express and reproduce from what they previously conceived with their intellect." - Leonardo da Vinci

The great Renaissance biographer and painter Giorgio Vasari wrote of Leonardo da Vinci that, in the last moments of his life, he rebuked himself for having “offended God and mankind in not having worked at his art as he should have”.

Da Vinci completed only about 20 paintings, but he left behind over 7,200 notebook pages, an accomplishment that reflects his unequaled range of intellectual passions.

He was born in 1452, near the town of Vinci, just outside of Florence, Italy. He was an illegitimate child to a notary father and a peasant mother, and initially received training in the master workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio. Until his death at age 67 in 1519, and despite his prodigious output, Leonardo owned little and hardly worked.

He tended to move between projects, leaving many of them unfinished (the Battle of Anghiari being a prominent example). Sigmund Freud characterised this tendency as the encroachment and subsequent suppression of the artist by the scientific personality which distinguished his life.

Yet, Leonardo's skill and outlook earned him a great reputation, which only grew after his death, and it culminates in our understanding and appreciation of him as the archetypal Renaissance figure. This is what Vasari writes about the qualities exemplified in his work:

“...Nature so favoured him that, wherever he turned his thought, his mind, and his heart, he demonstrated with such divine inspiration that no one else was ever equal to him in the perfection, liveliness, vitality, excellence, and grace of his works."

He had elegance, finesse and neatness, and he enquired with unparalleled genius into the unity of nature and its variety of astonishing patterns. What is it that made da Vinci's mind special?

To answer this question, it's essential to examine the extent of his contributions to painting, anatomy and scientific drawing, neuroscience, and ultimately, the blueprint of the scientific mind (this latter part will be addressed in a subscriber-only afterword to follow later).

A full answer may not be possible to the aforementioned question. But nevertheless, unbundling and putting together certain ideas might reveal how the mind of that quintessential genius was always devising new things, and how we might be able to learn from him.

Leonardo as Artist

Da Vinci revered the sense of vision, and placed it as man's highest sense. He described the eye as "the window to the soul", and the most important basis of all experience. Vision's role, beyond providing fundamental perceptual knowledge, involves the artist's use of the faculty in faithfully interpreting nature:

"The painter's mind must of necessity enter into nature's mind in order to act as an interpreter between nature and art".

To peer into nature's mind, Da Vinci understood that the artist must learn the laws of reality and its manifestations as perspective. He conceived of perspective as the seeing of an object behind a sheet of glass, and by which a pyramidal cross section is cut by the glass; thus all points of perspective can be expressed by point, line, angle, surface, and body. He also devised three branches of perspective:

"...the first deals with the reasons of the [apparent] diminution of the volume of opaque bodies as they recede from the eye, and is known as Diminishing or Linear Perspective. The second contains the way in which colours vary as they recede from the eye. The third and last is concerned with how the outlines of objects [in a picture] ought to be less finished in proportion as they are remote."

These laws of perspective were to be kept in mind so that only what could be seen with certainty was depicted as certain; that which was seen with difficulty was to be made indefinite. Lines were to be blurred and suggestively left open. His drawings were only made of outlines and hatching marks in accordance with those laws, and yet they convey unrivalled volume and dynamism.

Leonardo's technique can thus be seen as a solution to the duality between abstraction, and a naturalistic interpretation of reality. This is best exemplified in some of his hydrodynamic and geological drawings. In them, he wanted to carry across the dynamic forces of nature, stones slowly shifting across the ages, as the roots of plants growing in the crevices were tearing those very stones out, moving them ever so slightly from the old place they once occupied. Water rapids rippling and creating vortices. In these images, amongst others, Leonardo shows that nature transforms everything.

His drawings convey movement and the moving figure in a style that possesses exemplary confidence and control over artistic tools. As a student of reality, in which he placed supreme trust in the instruction provided by the visible world, he carefully studied figures using his cross-hatching technique.

This allowed him not only to depict his close observations, but also to best old techniques in faithfully conveying distance, the intangible density of the atmosphere, and the idea that the world exists as a spatial continuum.

Leonardo divided the science of painting into drawing and shading, and it was for him the "true knowledge and legitimate issue of nature". There's a further passage in which he explains his thought process as to how the artist should best consider painting:

"...as subtle invention which brings philosophy and subtle speculation to the consideration of all forms - seas and plains, trees, animals, plants and flowers - which are surrounded by light and shade".

A detail from Saint John the Baptist by Leonardo da Vinci.

This is a philosophy that is evident more so in the Mona Lisa and Saint John the Baptist, than any of his other paintings. About the former, read what Vasari had to say:

"The eyes have the lustre and moisture always seen in living people, while around them are the lashes and all the reddish tones which cannot be produced without the greatest care. The eyebrows could not be more natural, for they represent the way the hair grows in the skin—thicker in some places and thinner in others, following the pores of the skin. The nose seems lifelike with its beautiful pink and tender nostrils. The mouth, with its opening joining the red of the lips to the flesh of the face, seemed to be real flesh rather than paint. Anyone who looked very attentively at the hollow of her throat would see her pulse beating: to tell the truth, it can be said that portrait was painted in a way that would cause every brave artist to tremble and fear, whoever he might be."

To breathe life into portraiture, anatomical details and structure were to be carefully extracted from reality itself, so that the mouth and the lips may be joined to the face as a continuous surface.

Only by seeing and learning from direct observation how each thing is formed can the artist learn to reproduce each part. And by faithfully combining parts that he has learnt how to draw, he may reproduce the whole. But he also knew that this process must be achieved step by step:

"The organ of sight is one of the quickest, and takes in at a single glance an infinite variety of forms; notwithstanding which, it cannot perfectly comprehend more than one object at a time. For example, the reader, at one look over this page, immediately perceives it full of different characters; but he cannot at the same moment distinguish each letter, much less can he comprehend their meaning. He must consider it word by word, and line by line, if he be desirous of forming a just notion of these characters. In like manner, if we wish to ascend to the top of an edifice, we must be content to advance step by step, otherwise we shall never be able to attain it."

Scientific Drawing & Anatomy

Leonardo was a student of reality; being the first to draw in the open air, he inquired into the cause and reason of all visible things, and can be described as a visual empiricist. While he was knowledgeable of the scientific literature of his time and what had come before, he kept himself free and unconstrained by past thinkers. He accepted those things only which he could prove by the direct perception of his own eyes.

In his drawing "The Star of Bethlehem", he is able to depict the power of growth inherent in plants, the elasticity of twigs; and the correct observation and order of spiral shapes found in nature. There exists in them a combinatorial understanding of morphology and function of physiological principles that govern life. His drawings extract the "atmosphere of life" and make plants and animals look alive, since he is able to visualise the macro forces which we might characterise as the engine of life itself.

Leonardo thought of life as both a mechanism and organism. He thought of the earth as possessing a "spirit of growth"; and the soil as the flesh, its rocks as bones, limestone as the cartilage and "its blood, the springs of water".

The motion of animals, the major one found in nature he called "serpegiamento", or snake-like. It is a movement that he studied extensively and can be seen in the animal drawings, from horses to cats and fantastical dragons.

He used drawing to convey scientific knowledge (the empiricism aspect). Regarding the capturing of man in his anatomical studies, he warned against description without visualisation:

"And you who wish to represent by words the form of man and all the aspects of his membrification, get away from that idea. For the more minutely you describe, the more you will confuse the mind of the reader and the more you will prevent him from a knowledge of the thing described. And so it is necessary to draw and to describe".

Leonardo's concept of drawing meant a new era for the human mind had emerged. Had his notebooks been published during his lifetime, or even the anatomical treatises he set out to complete but never did, the most profound revolution would have occurred in science. Yet, progress in anatomy was left to other great minds like Andreas Vesalius, with the publication of his treatise "On the Fabric of the Human Body in Seven Books".

On anatomy, Leonardo advised that the painter should be,

"...thoroughly familiar with the limbs in all the positions and actions of which they are capable, in the nude. [Then he will] know the anatomy of the sinews, bones, muscles, and tendons so that, in their various movements and exertions, he may know which nerve or muscle is the cause of each movement and show those only as prominent and thickened..."

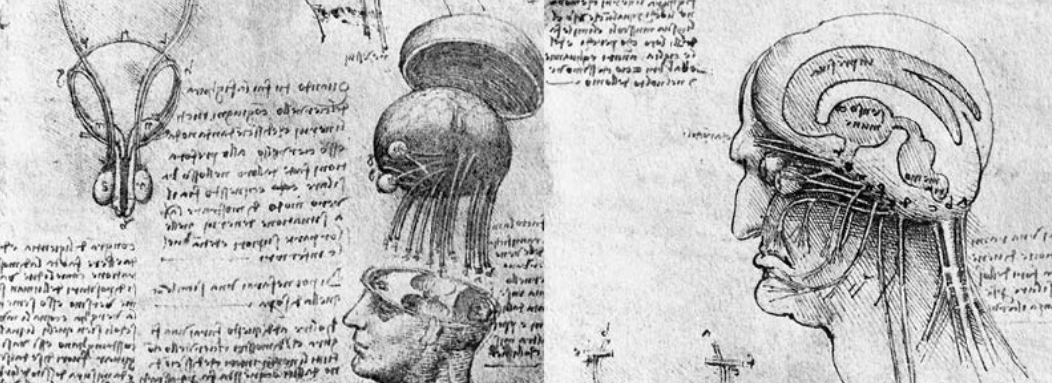

Contributions to Neuroscience

Beyond his pioneering work in painting, anatomy and scientific drawing, Leonardo wanted to prove that the mind has a physical basis. He wished to show the mechanisms by which the brain makes sensory stimuli intelligible, and thus show the functioning of the mind.

A few of his drawings depict three ventricles in the brain, cavities filled with cerebrospinal fluid, the first being responsible for the processing of sensory stimuli; the second housing thought and the integration of the senses; and the last ventricle by means of which thought and sensation are imprinted into memory.

The second ventricle is depicted as being in the geometric centre of the brain, thus denoting "the locus of the soul". This for Da Vinci was the place where the senses came together to form the "sense communis", or common sense, the seat of universal judgment:

"The soul apparently resides in the seat of the judgment, and the judgment apparently resides in the place where all the senses meet, which is called the common sense."

While this theory is known to be false, since we know the physical basis of the mind rests on electro-chemical communication between specialised neurons, it is nevertheless a triumph of his era, since he went beyond anything that had been put forward before.

To conclude, let's read an extract from Otto Benesch's essay, Leonardo da Vinci and Scientific Drawing (1943) that captures some aspects of his genius (and the likes of which I hope humanity will see again):

"This vision of cosmic grandeur reveals the deep intuition of the artistic genius. Leonardo's scientific insight is unthinkable without his artistic imagination. The artist and the scientist are interdependent. Leonardo possessed not only the masculine sovereign and creative power, but also the feminine gift of highest empathy. He lived in the heart of things. His drawings prove that he felt like the object which he portrayed, that he identified himself with it. He looked at the world from the center, from the matrix, and it became diaphanous to him in an almost magic clearness. Thus, both intuition and divination served as guides for this greatest intellect among the artists in his scientific accomplishments."