Tuesday, January 7, 2025

A selection of drawings from Leonardo da Vinci's notebooks.

“The senses are of the earth; reason stands apart from them in contemplation.” - Leonardo da Vinci

‘Libri di bottega’ translates to something like ‘work books’ or ‘workshop books’. Leonardo da Vinci obtained the practice of using ‘libri di bottega’ - notebooks that combine notes, sketches, models and records for consultation - during his training with Verocchio.

In December 2024, I wrote about da Vinci’s view of the world. In this post, I want to delve deeper into his notebooks.

The libri di bottega are instruments for expression. Because of their flexible typology, it meant that da Vinci could use the workbooks as a repository for creative ideas, a place which could provide continuity for visual exercises and creative thoughts, and a means of practicing for fresh sketches. The workbooks are moreover anthologies of motifs, written reminders and sketches.

Drawing was thus to be used as an instrument of cognitive investigation - to fix in place teaching furnished by experience; the suggestion of forms upon the mind; and the depiction of the curved and parallel lines which make up everything in the world. His drawings also play with hazy colours and outlines to depict distances; perspective was also given by colour, by the fact that colour fades in the distance.

Sketching for him was a motive for ongoing thinking. He used them to derive life-like movement and gestures to communicate “atti mentali” - the mental acts of subjects.

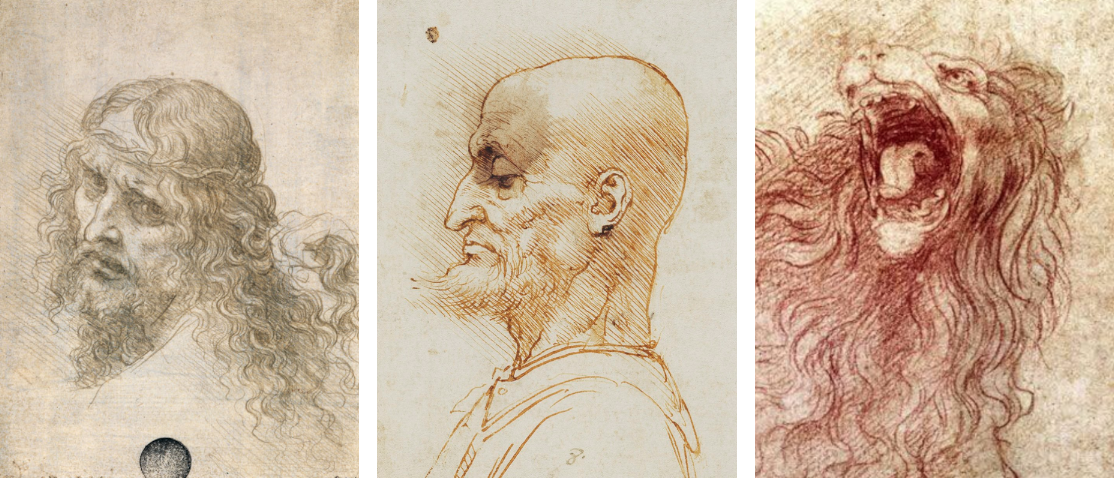

Head and shoulders of a Christ figure (c. 1490-1495); bald man in profile (c. 1495); and roaring lion (c. ?).

Drawings and sketches were “short signs” of bigger ideas, and hence why his uncultivated compositions placed a focus on the mental acts of figures, people and animals instead of a focus on the limbs. Leonardo writes:

“Therefore, painter, roughly compose the limbs of your figures and first attend to the movements appropriate to the mental accidents (acts) of the animals who compose the story, rather than to the beauty of and goodness of their limbs.”

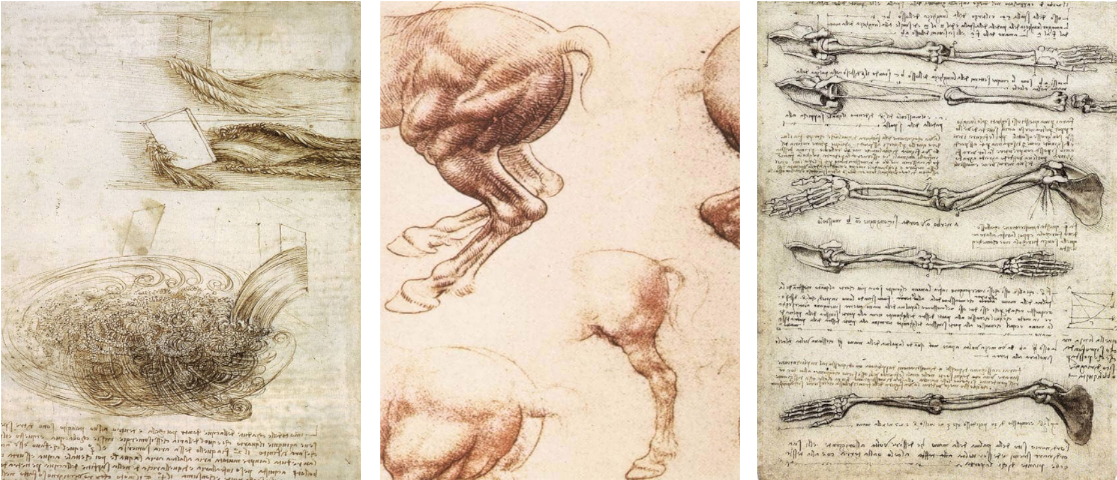

He studied the dynamic rhythms of life, and the aboriginal forces of nature which destroy everything: waves, whirls, spirals, centrifugal and centripetal forces. He saw these as the vital values inherent in nature, as its creative impulses, and as its way of the continuous transformation of forms.

Studies of water flowing past obstacles and sketch of whirlpool (c. 1508-1510); study of horse (c. 1503); and anatomical studies on the rotation of the arm (c. 1509-1510).

Leonardo saw the world in terms of laws - ‘reasons’ that govern nature, and the mechanisms which underlie it. The relationship between cause and affect was always on his mind.

Leonardo referred to nature as the “mistress of all mistresses”. In order to make works of any significance, the artist should not imitate but only take nature as the standard. Nature, experience and direct observation were the cornerstones of his method. The principles which regulate nature were indispensable to his production of art.

He was also a student of metamorphosis; the changing aspects of the world. He saw the genetic proceedings in nature and as that which forms its history. His sketches depict a clear train of thought: scientific analysis and artistic synthesis both lend to each other. For instance, he understood geological processes as the “chain of the world”. He wanted to take as his task the investigation and visualisation of the productive forces of the world.

Da Vinci subjected everything to an inquisitive gaze. His drawings have vibrancy, dynamism, analysis of morphology; the definition of forms are subjects to his understanding of the laws of reality and perspective (e.g. the disappearance of figures as they recede into the distance).

He could give a sense of breadth of landscape; a breeze moving through the trees, and the roar and motion of the waterfall. Nature was thus to be observed not as a background to life’s happenings; but instead the very dynamic force which brings forth everything.

As the only Renaissance author to allude to sketchbooks, he deemed them important for close observations from nature. He revisited themes ‘ex novo’, meaning from the beginning, as is evidenced by his animal and anatomical drawings.

Studies of the paw of a dog or wolf (c. 1480); study of the proportions of a dog's head (c. 1497-1499); and study of the proportions of a horse's leg (c. 1485-1490).

Leonardo above all understood the necessity of technical spontaneity and virtuosity. He was aware of the role required by both the conscious and unconscious mind in the creative impulse.

In the dazzling quick sketches that he produced, he allowed the creative imagination to be released through that process of rapid sketching and the brainstorming of ideas. He was also aware of the creative energy that is evident in an unfinished work of art. He owned a copy of Leon Battista Alberti’s work, De Pictura, in which Alberti says:

“It is advisable to avoid that decadence of those who, wanting everything to be free from every defect and everything to be too clean, in their hands the work becomes old and dirty before it is finished.”

For ultimately, Leonardo wanted to capture in his drawings the convergence of sensory perception and the phenomena and movement of the world. Hence why his drawings often do not provide too much detail, but instead allude to the fact that, in them, an inquisitive mind is subjectively investigating the world.